ANDERSWO/ELSEWHERE

Published by Schiltpublishing 2021

My photographs gathered together within Anderswo / Elsewhere reveal the small but cherished observations which have enriched my life and celebrates the people who shared their experiences with me on my journeys. Size 9.5” * 9.5” .

Credit for photographs and videos of all the photographic material on this site goes to Dante Busquet, Berlin

Essays

Author PETRA BARTH WASHINGTON, D.C., BERLIN, GERMANY, July 2020 and

Author Bill Kouwenhoven Baltimore, 12 July 2020

ANDERSWO/ELSEWHERE

Part I

I grew up in a rural village. My sisters and I lived with our parents on a small piece of land where nature was untamed. We climbed trees and floated on tires in big puddles of rainwater. We picked wild blueberries in a nearby forest, and for dinner my mom served them in a big bowl, topped with cold milk and a piece of bread and butter sticking out.

On the other side of the street was a massive potato field. I wandered along the giant furrows that were cut deep enough so the roots wouldn’t tangle and could be easily harvested. Often, I stayed for hours, before I crossed the street again.

Then, as the evening approached, I feared for the moment we had to get ready for bed. Recurring nightmares haunted me during the day and kept me awake at night. I kept hoping that if I didn’t fall asleep, I could escape my dreams.

Maybe that’s why I am captivated by illusions.

My mom would hang the clothes my sisters and I would wear the next morning on the closet door. How was she to know that they threw ominous shadows that danced across the room, intensified by the light of the moon shining through our tiny window?

Maybe that’s why I am fascinated by shadow and light.

When the sun rose across the street, behind the field over the hilly line at the horizon, we roamed the land and looked for adventure, inspired by tales from faraway countries that our parents read to us at bedtime.

Maybe that’s why I am drawn to the countryside, and to the unknown.

Decades have passed since I was that little kid. My nightmares have faded and were replaced by curiosity. I have always wondered what is on the other side and far away from home. Through the lens of my camera, I am able to explore it and keep moments alive which otherwise would be forgotten. I am interested in small things but also vast landscapes and often wander off the beaten path to find the unexpected.

Once, on a bitterly cold day, standing on the bank of the Yukon River, I began to see the invisible. Human shadows, snowflakes, the river, a few dead animals, even a part of myself—there, through the lens of my camera, I could not separate the real from the unreal. I lifted my eyes and found that everything I had just seen, distorted and distant, was gone, and the river was only a couple of feet away. Then I looked again, trying to discern what I was seeing. But it was impossible. It was a blur, layer after layer melting together. I took my camera and pressed the shutter, focusing on one minute spot. And there it was again, compressed and blended into a single image, all an illusion.

The images in ANDERSWO reflect where I have traveled to, what I have seen, and what I have experienced. A journey to unfamiliar places, both geographically and emotionally. They reveal important moments in my life.

Over the many years that I created this body of work, my thoughts kept shifting to the past, my own memories interweaving with the stories I listened to others share. I followed intangible threads without knowing where they would take me. In the end, they led me back to the little girl in the potato field, captivated by the unpredictable.

Part II

I was standing next to my grandmother, my head at the same height as the blue enameled pot on the stove, the smell of deep-fried treats surrounding her. When the waffles turned golden, my grandmother lifted them from the bubbling oil and covered them with a mixture of cinnamon and sugar. She placed them on a plate on the little kitchen table, which was covered with a handstitched tablecloth and set with dishes and cups. My cup was like a small goblet, painted with a golden rim and blue wildflowers. It was filled with hot chocolate topped with a crown of heavy whipped cream that dripped over the edge, spreading onto the beautiful white linen tablecloth.

Sitting at the table, my grandmother gazed in the distance. A survivor of two world wars, she had seen everything, and memories of the past wafted into the present. Perhaps I have been too little to grasp the magnitude of the events, but the pain in my grandmother’s eyes was impossible for me to miss.

Then my grandmother turned to me and started talking, about her sister, whom she had lost at the age of fourteen, and her brother, who had died in a fire after a series of air raids in Nuremberg. It was on January 2, 1945, she said, when she took her nine-year-old son and walked for miles to find her brother. On reaching the street where her brother had a little shop, she realized there was no hope. The street – the whole city in front of them – had risen in flames, nothing but fire and smoke. Holding her son’s hand, she turned around and walked all the way back home between rubble and ashes.

Shortly after, the war came to an end, and she found herself for the second time in her life on the side of the defeated. The next year hit Germany hard: Freezing temperatures paired with a lack of food shook the country, bringing disease and more death. But gradually life came back to the streets, and she started her own business as a seamstress, while her son delivered newspapers and ran errands for the Americans.

Her son met a beautiful young woman, who, like his mother, had learned the craft of sewing. He married her and brought her home, to the land where he had spent his childhood. His wife had seen the war as well, and her experience was as horrifying as his own. Seldom did they share their memories. Still too fresh in their minds, they tried to forget. Years later, when they had their own children and the war seemed far away, he sometimes talked about the day he walked with his mother to find his uncle.

He moved with his wife and two little girls into a small apartment under the attic, above the factory where he sat every morning at the old walnut roll-top desk that had once belonged to his grandfather. When he added the numbers, he often wondered if he would be able to write the paychecks at the end of the week. His wife stood at a long table close by, drawing thick lines with white charcoal on the textiles that would be cut and sewn and would finally fill someone’s closet. He believed that sometime in the future he could build a home for his family.

Much of the time, the girls were off by themselves. They hid in the big metal shelves stacked with bales of fabric. They created miniature worlds under the inclined ceiling of the attic. They told each other boundless fantasies, inspired by the tales they heard at night: stories from faraway countries, the good and the bad. On Sunday, when their grandparents came to visit, they looked at old photographs and listened to them reminisce.

I cherished the memories of both generations and kept all their stories in my mind. With my grandmother’s help, I started sewing too, a craft I later used in my career. In my free time, I devoured books from distant lands and mused about life across the ocean and beyond the horizon.

As I grew, I developed a clear mind, but I held onto a romantic imagination and an unrestrained desire to travel and see more. Sometimes my career required me to leave for weeks; sometimes I went only for a couple of days. I met many people and I listened to many stories. Some reminded me of the ones I had heard from my grandmother; others were new and unfamiliar, like the landscapes that changed as fast as the passing clouds.

One day I arrived in El Salvador. The earth was boiling, the temperature 120 degrees. The air flickered; the horizon was invisible. I walked for hours until I spotted some metal shacks with children playing in the shade. When I came closer, it was difficult to adjust my eyes from sun to shadow. I saw a mother and her little girl hiding from the heat, with a black dog behind them. Moments later others joined them. Despite the modest houses, everyone was nicely dressed, and the earth around was swept clean.

With the little Spanish I knew, I began to speak. When I asked if I could take some photographs, they agreed. I stayed in the village through the afternoon. I forgot everything else. That was the day I learned that when I connected with people, they would trust me with their stories.

Some memories have faded with time, but some are steadfast, because they remind me of my roots growing up in post-war Germany, listening to the stories of my grandmother while savoring waffles and hot chocolate.

© 2020 Petra Barth

Author Bill Kouwenhoven Baltimore, 12 July 2020

Illuminating the Shadows

In his Apology, Plato quotes the soon-to-be-famous dictum of Socrates, apparently uttered at the conclusion of his trial for impiety: “The unexamined life is not worth living.” I always misremembered this as “The unreflected life is not worth living,” a phrase that began to interest me more and more as I became deeply immersed in photography.

For what is photography but a form of reflection, one of writing with light reflecting on and affecting light-sensitive materials, whether silver salts or charge-coupled devices?

A photograph’s pixels reflect the impact of light that is itself reflected from the subject before the lens. This double reflection becomes a visual artifact, a form of memory of that moment and all that surrounded it--the photographer, the choice of camera, the subject, the distance between them, the nature of the light, and so on.

That photography produces “instant memories” does not mean that the photographic image is unmediated. It is always mediated, just as memories are but shadows of the reality of moments or events filtered through our human senses and the fleeting prisms of our experiences.

With conventional, film-based photography--newly retronymned as “analog” photography--light is passed through a negative, and the shadows it leaves as it is projected onto paper etch themselves into a positive image, a photograph.

The journeys the light takes as it moves back and forth—from sun to subject to camera, then from negative to positive--further reflect and refract, leaving the kinds of artifacts, tiny errors or greater ones, that afflict memory. There is no absolute, one-to-one correlation between subject and photograph, just as there is no exact correlation between an event and the memory of it.

All our attempts to force this correlation are a search for something impossible, but it is this examination that is its own fugitive driving force. However abstract or real a photograph may be, it is not the object it represents. But for the viewer, the attempt to illuminate these shadows is as much a search for truth about an object or event as it is a search for one’s self. As such, the journeys of light in photography parallel the journeys of memory as one reconstructs the moment of the photograph. And as photographs accumulate throughout a photographer’s career, they become steppingstones along the path of the photographer’s life, leading backward to something unseen: that flickering sense of self.

In the case of the photographs contained within the bindings of this book, the parallels between the outward journeys of the photographer, Petra Barth, and her search for her own sense of self are striking.

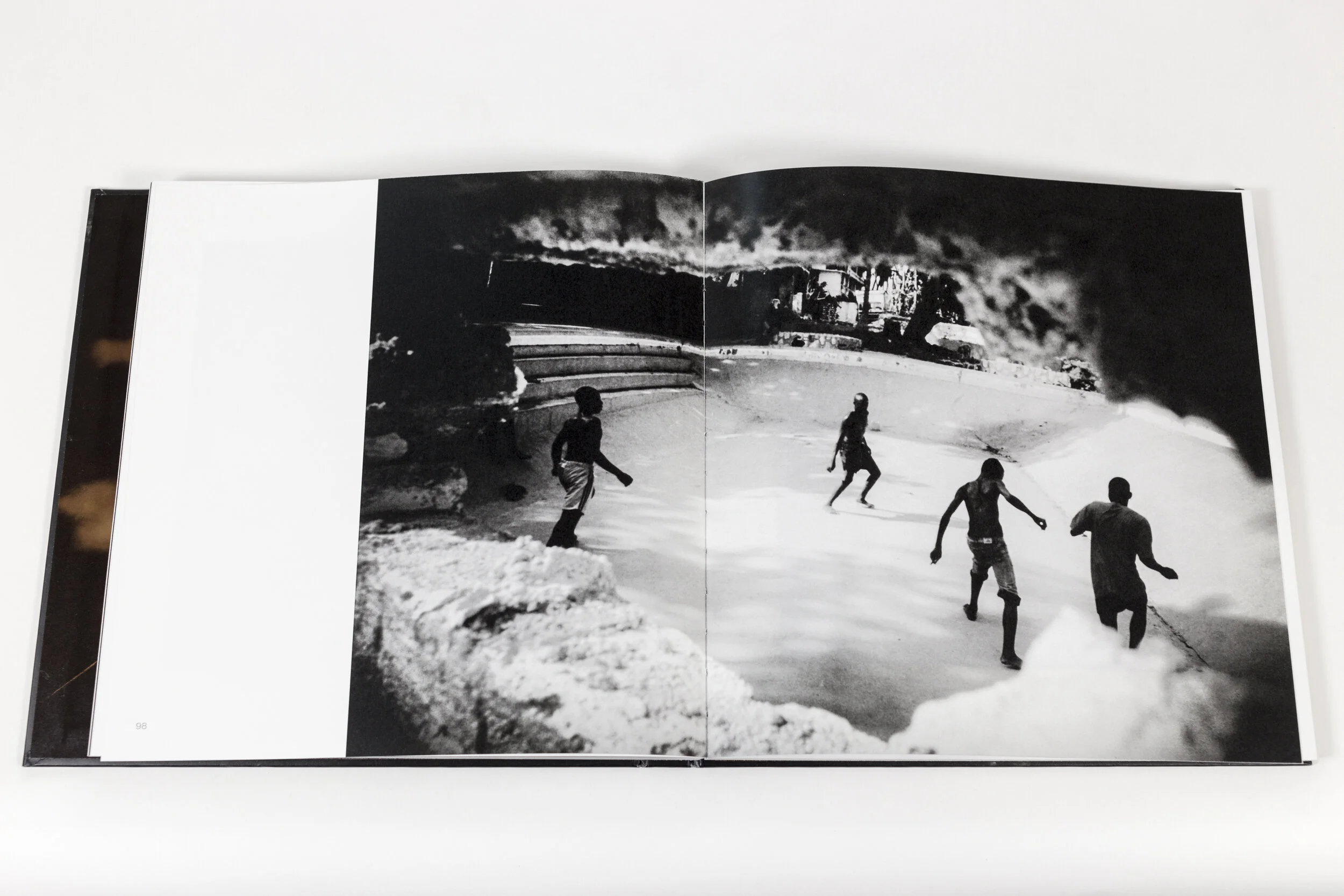

Taken over the course of the last 16 years and across four continents, these images inevitably mark the places where she has been, of course, but they are more than that. They share a visual continuity of style that manifests her life’s journey.

Enigmatically titled “Anderswo / Elsewhere,” the German and English title already places the beholder in a place that is neither here nor there but in some other place. Its in-betweenness reflects the in-betweenness of Barth, who has traveled and lived for extended periods far from her native Nuremberg, Germany

Barth came from a family in the textile business. Throughout her childhood, she would be taken to factories and fashion shows in Milan, Hong Kong, Paris, Hamburg, New York and beyond. She studied fashion design in Milan and worked in the industry for a time, picking up photography to capture memories.

Back in Germany, marriage and children followed, and a circuitous path took her to Washington, D.C., to find a school that could accommodate one of her children who needed learning therapies not available then in Nuremberg. As the children grew, she became more and more invested in photography, and her twin sister suggested she study it with more seriousness.

In Washington, she studied at what was then the Corcoran College of Art with critic Andy Grundberg and photographer Muriel Hasbun, among others. “The first class I took with Muriel was named ‘Identity and Place,’” Barth writes. “It was the class which, in retrospect, affected my work most. Never before had I thought about my identity or the place I grew up.”

Hasbun had grown up in El Salvador, and her work dealt with that past. Barth thought about their common experiences--moving to another country, speaking another language, living in another culture. “I suddenly faced the same questions. Where is my home? Where do I belong?”

This self-questioning was transformative and life-affirming. Hers became a life of photographs and memories.

Barth took a sojourn to Central America, where she had friends from Washington. She set out to work with an NGO in Managua, Nicaragua, and Iger, Guatemala, worlds she knew only from movies and books--especially the magical realism of Isabel Allende, Giaconda Belli, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez--but, more particularly, from Hasbun’s memory-inflected work.

In four months, she traveled from Costa Rica to Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. “In Nicaragua I photographed during the election of Ortega and observed firsthand the tense atmosphere throughout the community,” recalls Barth.

Photography workshops followed: in the United States, Cambodia, Russia, Italy, and Bosnia-Herzegovina. Barth would return to Germany every six weeks or so to reunite with her family, and sometimes her children traveled with her. Her workshops and other photographic odysseys affirmed her self-worth as well as bought her the time to “recover and reboot,” as she put it.

This fractured lifestyle might have led other photographers to produce a disparate collection of images. In the case of Barth, however, there is a coherence of visual motifs that link the works despite the vast distances across time and space that mark their creation.

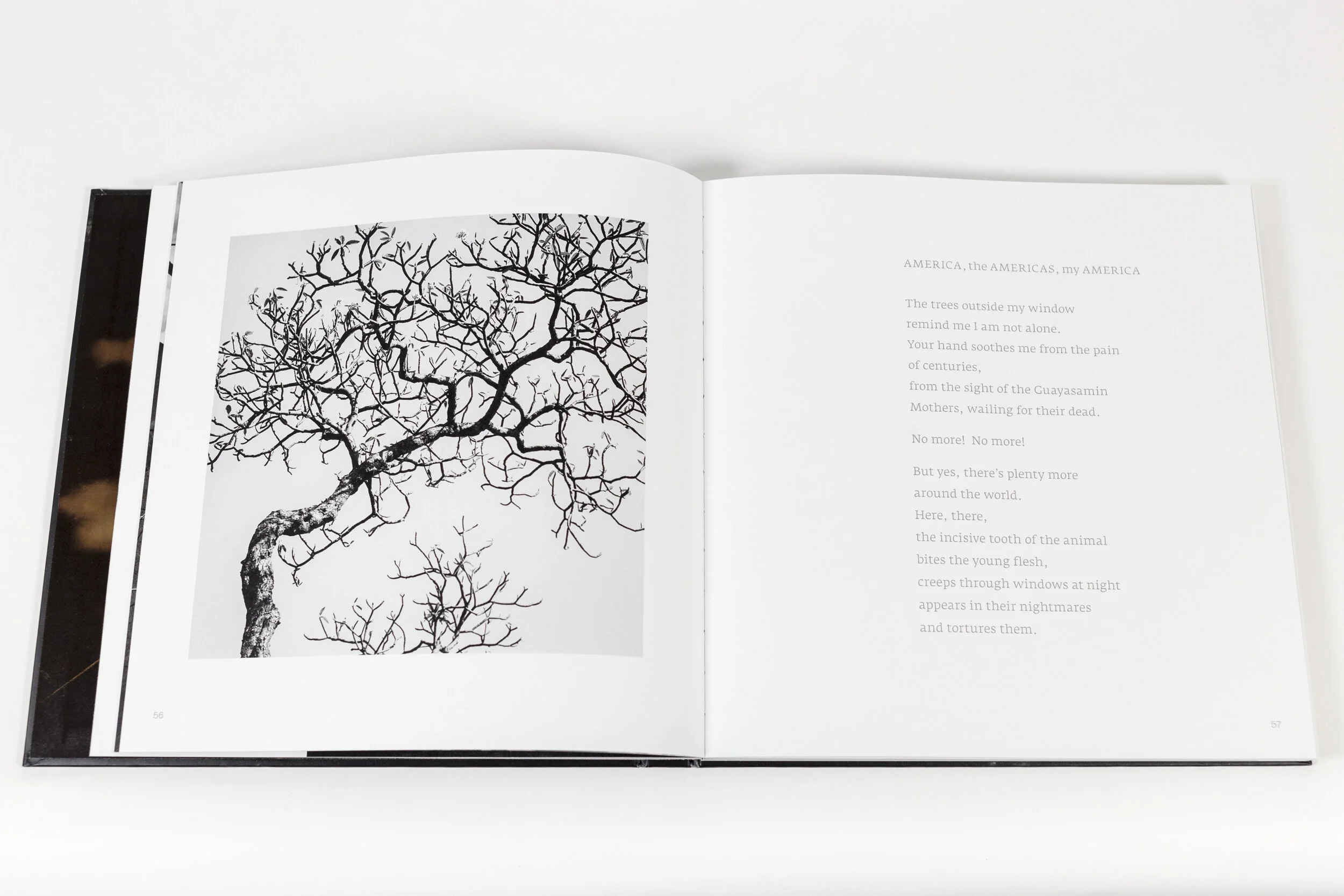

Her dense patterns of reflections and shadows, whether of houses or forests in India or Alaska, have the unsettling feeling of dreamscapes that cannot be placed. Intentionally, there is little text in her images, yet there are nearly always threads, wires, lines that indicate a path, as vague and as suggestive as those of the Greek goddess Ariadne’s that led Theseus out of the Minotaur’s labyrinth.

The lines and wires are also a metaphorical warp and weft of the fabrics created by her family and ever present in her life. Some images even contain linens or gauzy curtains through which light and shadows are alternately revealed and obscured.

The section titles in Barth’s book--“Memories,” “Stories,” “Dreams” -- provide a whirlpool of metaphorical images from the stages of her life. A book, of course, arranges things linearly so the gentle reader can be led on a journey. And family letters offer telling clues. One was written by a cousin more than 60 years after the event it describes: the traumatic firebombing of Nuremberg in 1945 that destroyed the city and killed Barth’s great-uncle.

Interwoven among the metaphorical images is the dreamy poetry of Milagros Terán, a good friend of Gioconda Belli, whose writing so influenced Barth. The poems seem to guide the reader’s interpretation of Barth’s memories and stories, her traumas and pleasures. But perhaps the guide is as errant as Hansel and Gretel’s breadcrumbs, and not as firm as Ariadne’s.

There are images of children and families, again some grounded in particular locations and some in uncertain settings, reflecting Barth’s experiences. Windows open out and in, faces gaze out and in at things unseen. Roads lead from the past and into the future, but always from no fixed place, just as they do in the best fairy tales. To how many elsewheres do they lead?

Indeed, the whole progress of this collection of photographs presents a river of shadows that only slowly lets itself be revealed as the story of Petra Barth’s journey. The motifs and other clues she leaves in her images, the pattern of the fabrics, the similar graffiti on a wall, the various lines, all help illuminate the shadows that obscured her search

© 2020 Bill Kouwenhoven

First published in ANDERSWO / ELSEWHERE, Fall, 2020